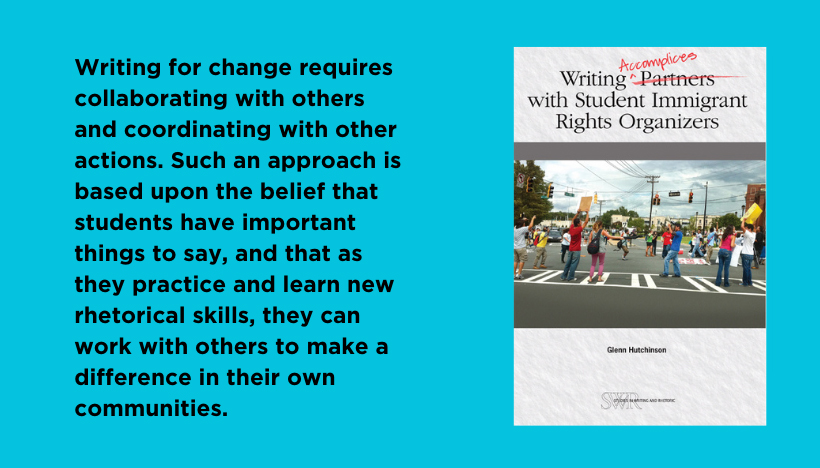

This post was written by NCTE member Glenn Hutchinson, the author of Writing Accomplices with Student Immigrant Rights Organizers (CCCC Studies in Writing & Rhetoric (SWR) Series, 2021).

Working with student organizers in the immigrant rights movement has helped me revise my community writing syllabus into something more focused on students and their abilities as change agents.

When my friend’s brother received an order of deportation even though he had lived in the US since the age of three, student organizers helped organize and stop his deportation. When undocumented students were forced to pay three times the amount for tuition even though many had lived in Florida since they were children, student organizers worked to change this policy so that more students can attend college. And there are many more examples of young people organizing to challenge antiimmigrant policies as administrations from both political parties continue to deport and exploit immigrants.

But when I first started teaching, I assumed that student experiences were similar to my own. My first community writing course, for example, often explored questions about voting and citizenship; however, my curriculum design did not acknowledge the reality that many students and their families were prevented from becoming citizens because of their immigration status. My initial syllabus lacked readings about a number of topics, including intersectionality and racism. There were no texts authored by student organizers. Guest speakers tended to be only representatives of nonprofits, professors, or politicians. In addition, the structure of the assignments focused on volunteering a set number of hours for a nonprofit and encouraging students to define what being an active citizen is.

Students have helped me critique and shape this syllabus into something more responsive to student needs. In the revised syllabus, published writings by organizers like Prerna Lal and Tania Unzueta, Angelica Velazquillo, Nicolas Wulff, Thomas Kennedy, and Gaby Pacheco play a central role. In contrast with the original syllabus, there isn’t a specific number of hours that a student needs to volunteer. In this newer version, students work individually or in groups to address a community project that interests them and, based on that project, determine what kind of writing might be appropriate. Some students may join the organizing efforts discussed by guest speakers, and others may work together to be part of new projects. This syllabus continues to be modified based on student concerns and input.

Here are some guiding principles for my syllabus revision:

- Rethinking the role of the writing teacher

Rather than just being an ally with others, the writing teacher may need to take more risks, or be what more scholars in our field, including Aja Martinez, call an accomplice. It is not enough just to wear a pin on one’s shirt to indicate support; teachers have an ethical responsibility to stand in solidarity with students working for equal rights. This is not an easy role to define, and it may vary depending on a teacher’s positionality.

Asao B. Inoue challenges white teachers to change the way they teach and end “white language supremacy” in the classroom. Carmen Kynard urges scholars and teachers to ask how their work responds to injustices like the violence against people of color. Sara del Pilar Alvarez highlights the complex literacies of immigrant rights organizers as she discusses the distinctive qualities in their writing, or what she calls “conciencia bilingüe.”

In addition, for teachers like me who may never have questioned their own assumptions about citizenship, identity, and the American Dream, it is important to decenter our own perspectives in designing the curriculum for a community writing course and reimagine what our roles can be.

- This framework isn’t based on one single issue; it’s a process of long-term organizing.

This approach moves past an individualistic mindset that all we need are more individual volunteers and writers to address a particular social issue. Student organizers often emphasize the importance of organizing not just to address one particular issue, but for people to come together for multiple concerns. At a moment when democracy faces even more challenges with a shrinking public sphere, organizing offers possibilities for a better future when more people’s voices are heard.

- Writing is part of a network of action to create change.

Writing assignments, then, become more than individual pieces written for one particular moment. Writing for change requires collaborating with others and coordinating with other actions (petitions, letters, rallies). Such an approach is based upon the belief that students have important things to say, and that as they practice and learn new rhetorical skills, they can work with others to make a difference in their own communities.

In this work, student organizers write op-eds, petitions, and press releases. They organize press conferences, rallies, and protests. And they often use writing as part of a network of action to address problems in their communities.

Our field has a wealth of scholarship about community engagement, and student organizers’ input can build upon this work. Writing Accomplices with Student Immigrant Rights Organizers argues that we need to make the writing and work of student immigrant rights organizers more central to the classroom and the field’s scholarship.

Glenn Hutchinson teaches rhetoric and composition and directs the Writing Center at Florida International University in Miami. Since 2007, he has volunteered with immigrant rights groups in North Carolina and Florida. His book Writing Accomplices with Student Immigrant Rights Organizers was published this year by NCTE. He has also published articles in Community Literacy Journal, The CEA Critic, and Reflections, and writes plays and op-eds.

Glenn Hutchinson teaches rhetoric and composition and directs the Writing Center at Florida International University in Miami. Since 2007, he has volunteered with immigrant rights groups in North Carolina and Florida. His book Writing Accomplices with Student Immigrant Rights Organizers was published this year by NCTE. He has also published articles in Community Literacy Journal, The CEA Critic, and Reflections, and writes plays and op-eds.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.