This is an excerpt from Chapter 1, “Black Language Is Good on Any MLK Boulevard,” of Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy by April Baker-Bell (NCTE-Routledge Research Series, 2020).

Despite growing up loving Black Language, I did not develop a full understanding of language politics until I started teaching English Language Arts (ELA) at a high school on the eastside of Detroit, which is really a damn shame given (1) the legacy of Dr. G aka Geneva Smitherman’s pioneering work on Black Language in Detroit and around the world; (2) some of the most influential Black Language research happened in the D (see Wolfram, 1969; also see Smitherman’s foreword of this book); and (3) the landmark 1977 Ann Arbor Black English case took place in Ann Arbor, Michigan—only an hour away from where I grew up and taught (see Smitherman, 1981, 2006).

There really is not a legit reason why any teacher in the state of Michigan should walk out of a teacher education program unaware and ill-prepared to address Black Language in their classrooms, but here we are! This is why Linguistic Justice is personal. I see this book as an opportunity to speak back to my 22-year-old self, a young Black teacher who wanted to enact what bell hooks describes as a revolutionary pedagogy of resistance—a way of thinking about pedagogy in relation to the practice of freedom. I would have never imagined that the preparation (or lack thereof) that I received from my teacher education program would contribute to me reproducing the same racial and linguistic inequities I was hoping to dismantle.

To keep it all the way real, I credit my students for my entry into what Dr. G refers to as the “language wars.” Just like most Black people who lived in the D, the students I worked with communicated in Black Language as their primary language—it was reflected in their speech and writing.

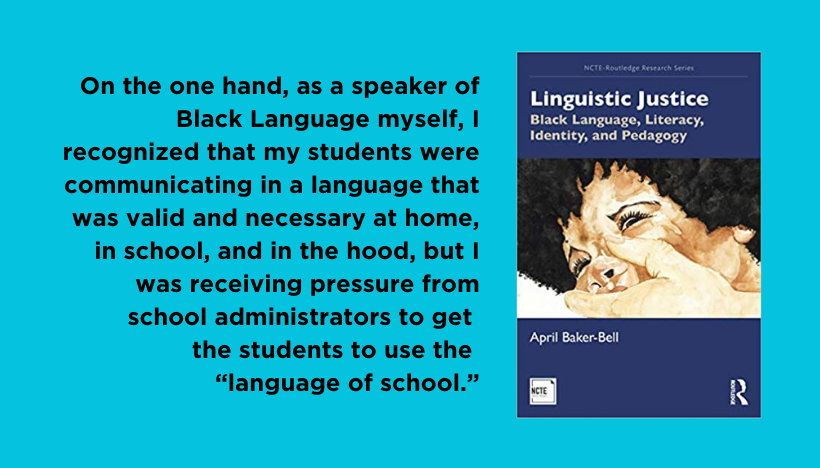

On the one hand, as a speaker of Black Language myself, I recognized that my students were communicating in a language that was valid and necessary at home, in school, and in the hood, but I was receiving pressure from school administrators to get the students to use the “language of school.”

I personally found this problematic given that the language arts methods that I received from my teacher education program catered to native speakers of White Mainstream English and assumed that every student entering ELA classrooms spoke this way. At that time, I did not have the language to name the white linguistic hegemony that was embedded in our disciplinary discourses, pedagogical practices, and theories of language, nor did I have the tools to engage my students in critical conversations about Anti-Black Linguistic Racism. I can still recall having a conversation with students in one of my ELA classes about code-switching when one of them flat out said, “What I look like using standard English? It don’t even sound right.” Other students joined in and insinuated that using “standard English” made them feel like they were being forced to “talk white” and many questioned why they had to communicate in a language that was not reflective of their culture or linguistic backgrounds.

My own cultural competence as a Black Language-speaker knew my students were speaking nothing but the TRUTH, but as a classroom teacher, I was ill-equipped to address the critical linguistic issues that they were raising. What I learned early on in my teaching career was that many of my Black students resisted the standard language ideology because they felt it reflected white linguistic and cultural norms, and some of them were not interested in imitating a culture they did not consider themselves to be a part of.

As I continued my teaching journey, I became interested in understanding the language wars outside the contexts of my own experiences. I visited other schools and classrooms in Detroit and its surrounding areas to inquire about how other teachers were responding pedagogically to their Black students’ language practices.

I learned that some classrooms operated as cultural and linguistic battlegrounds instead of havens where students’ language practices were affirmed, valued, and sustained. I listened to stories from teachers who faulted, punished, and belittled their students for showing up to school with a language that was deemed incompatible with the literacy conventions expected in the academic setting. As I compared these practices to the counterstories I was hearing from Black students about the deficit and culturally irrelevant language education they were receiving in schools, I found it important to speak back to these injustices by working at the intersections of theory and praxis.

Dr. April Baker-Bell is a transdisciplinary teacher-researcher-activist and Associate Professor of Language, Literacy, and English Education in the Department of English and Department of African American and African Studies at Michigan State University. A national leader in conversations on Black Language education, her research interrogates the intersections of Black language and literacies, anti-Black racism, and antiracist pedagogies. Baker-Bell’s award-winning book, Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy, was co-published with Routledge and NCTE Books in May 2020. Baker-Bell is the recipient of many awards and fellowships, including the 2021 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s New Directions Fellowship, the 2021 Michigan State University’s Community Engagement Scholarship Award, and the 2020 NCTE George Orwell Award for Distinguished Contribution to Honesty and Clarity in Public Language. Twitter: @aprilbakerbell.

Visit the NCTE Store to learn more or order Linguistic Justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.