From NCTE’s Standing Committee on Global Citizenship

This post was written by NCTE member Chase Eddington, who is also a member of the Standing Committee on Global Citizenship.

English language classrooms benefit from reading texts from many languages. Reading translated texts with intention can encourage students to think deeply and creatively about writing, meaning, and the nature of language.

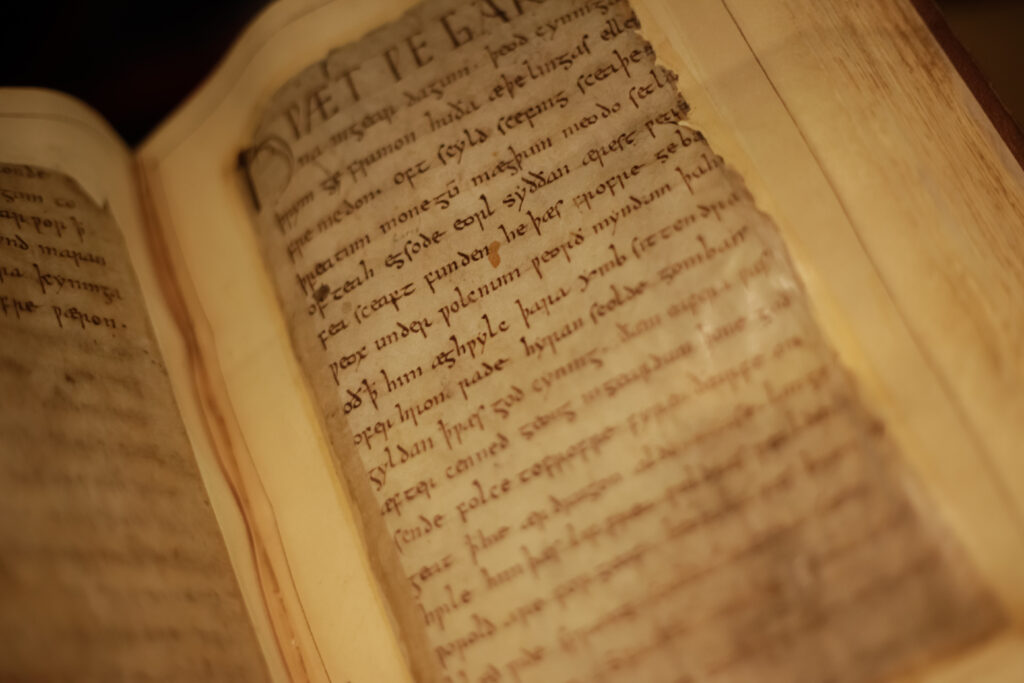

Consider the perennial difficulty around translating the word hwæt, the interjection that begins Beowulf. Dozens of translators, from at least John Kemble’s 1837 version of the poem, opted for translating it as “Lo!” John Earle, in 1892, went slangily Victorian with “What ho!” Seamus Heaney chose, poetically, “So!” and Maria Dahvana Headley’s provocative translation opens with “Bro!” Some translators look to recapture the specific meaning of the word—which is difficult when a precise one-to-one translation does not exist, as in the case of hwæt—while others look to the poetry, intent, or cadence of the original, even if their chosen word doesn’t capture the same meaning. Within the past ten years, Old English scholars, led by George Walkden of the University of Konstanz, have resituated our understanding of the word hwæt by suggesting it does not function as an interjection at all, but as a pronoun that introduces an exclamative clause. Therefore, the opening of Beowulf might be more accurately presented without including any interjection at all to begin the poem—it simply needs an exclamation point at the end. Won’t this change in translation, though, affect the modern English language reader’s experience of the poem?

Well, yes. These variations in word choice affect the meaning of the text, and they can potentially alter a reader’s perception of the text as well. Perhaps the better question to ask is whether the reader’s experience is more dependent on the source material or the translation available in her language. Thankfully, the answer here isn’t binary, and the spectrum of interpretation has the potential to open discussions in the classroom in compelling ways.

Students benefit from engaging in the process of translation, whether they’re analyzing how a text is translated or translating some text themselves. Engaging with the process of translation, in addition to simply reading translated texts, challenges students to think deeply about the many perspectives of which they must take stock when reading translated texts, including that of the source language author, the translator, and the reader. The perspectives and knowledge of each of these people affect how meaning is shared and received.

I want to share two ways I approach integrating the challenges of translation into the English classroom:

Read Multiple Translations of the Same Selected Texts

Sticking with Beowulf a moment longer here, consider an excerpt from three different recent translations. In the opening of this scene, Grendel is introduced as a threat to Heorot’s peace:

Seamus Heaney (W.W. Norton, 2000):

Then a powerful demon, a prowler through the dark,

nursed a hard grievance. It harrowed him

to hear the din of the loud banquet

every day in the hall

Stephen Mitchell (Yale, 2017):

Then the fierce demon who prowled in darkness

suffered torment: it tore at his heart

to hear rejoicing in the hall

Maria Dahvana Headley (FSG, 2020):

Speaking of grudges: out there in the dark, one waited.

He listened, holding himself hard to home,

but he’d been lonely too long, brotherless,

sludge-stranded.

Ask students to discuss the shades of meaning between the different translations. Heaney has Grendel here, “nurs[ing] a hard grievance.” How is that different from “suffering torment”? Or holding a “grudge”? The translator’s choice in word, as we can see in evidence here, does not only affect the cadence and musicality of the poem, but it can also affect how we read and react to the characters within the text itself. Are we, as readers, more sympathetic to a sufferer of torment or a bearer of a grudge? How might our introduction to Grendel as sympathetic or not affect our reading of the text as we continue?

In my experience, where multiple translations of a text are available, students capably distinguish between the subtleties of meaning between different translations, and, as a result, they tend to read texts more closely and analytically, offering lively discussions on their preferences for the best or most effective versions.

Engage in the Translation Process

As students develop close reading and analysis skills, task them to translate a text independently. Translated haiku are especially good candidates for this activity. Can we, as students, rewrite a translated haiku while both preserving the meaning of the poem and its structure? Students quickly realize how thorny a problem translation can be: the precise word may destroy the cadence or structure of the haiku, but an approximate, imprecise word may fit perfectly. This activity asks the would-be translator to consider the intent and purpose of the text’s original author while simultaneously considering the language within the student’s own vocabulary that could achieve the original author’s aims without sacrificing content or meaning.

Going back to the Beowulf excerpts above, how might students rewrite this section? Are they trying to preserve the alliterative function of Old English? Make Grendel sympathetic? Or monstrous?

To develop a global perspective, students should read globally; to read globally, students should understand and consider all the challenges the translator faces. In the end, reading translated works in the English classroom in conjunction with thinking deeply about the process of translation encourages students to read texts closely, analyze them, and understand better the experiences and intentions of people different from themselves.

Aaron Chase Eddington is the director of development and communication at the Selwyn School in Argyle, Texas, where he also teaches sophomore English. He serves on NCTE’s Standing Committee on Global Citizenship.

The Standing Committee on Global Citizenship works to identify and address issues of broad concern to NCTE members interested in promoting global citizenship and connections across global contexts within the council and within members’ teaching contexts.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.