From the NCTE Standing Committee on Literacy Assessment

This post was written by NCTE members Kathryn Pierce and Chris Hass, members of the NCTE Standing Committee on Literacy Assessment.

For many teachers, one of the bright spots during the pandemic has been a suspension of statewide standardized testing.

The absence of annual testing data highlights the work teachers do every day to gather student learning data through observations, interactions, and consideration of student products. Like a translator, teachers simultaneously teach while processing all this data, making adjustments “on the fly.”

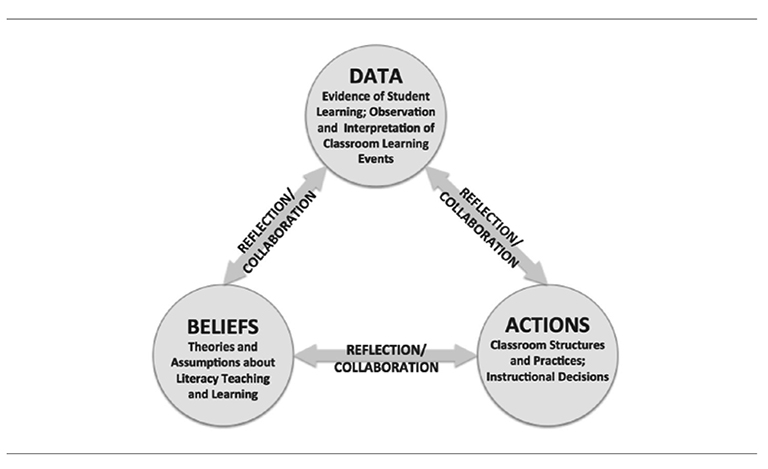

One way to help manage the flood of data is to be intentional about articulating goals and intentions and to make space for students to do the same. The diagram below (from Going Public with Assessment) shows how our instructional decisions are connected to our beliefs and to the data we collect about students. It also shows how we interpret the data we collect through the lens of our beliefs and our instructional intentions.

Transactional Model of Professional Growth, pg. xix. Pierce, K.M. & Ordoñez-Jasis, R. (2018). Going Public with Assessment: A Community Practice Approach, National Council of Teachers of English.

Another way we manage the data is to be intentional about what data we collect and the questions we ask about that data. Based on our beliefs about how literacy/language works and how best to support literacy learners, we make instructional decisions. For example, we protect time for silent reading or support students in seeing writing as a process that evolves across multiple drafts.

In this blog post we offer procedures and questions that may guide our use of observations, student learning artifacts, and conferences with students as intentional assessment experiences.

Turning Observations into Intentional Assessment Opportunities

Teachers watch their students as they read and write, and talk with classmates. We listen in for signals that all is well, or that support may be needed. Creating kidwatching notes by jotting down observations focused on a specific topic or on general observations allows us to revisit this information again later.

Click HERE to see an example of kidwatching notes from Chris Hass’s classroom in which he both collects data about their reading process (narrative notetaking) and their perceived engagement during independent reading (checklist).

How might we use these observations for assessment purposes?

Click HERE to see one way of preparing for intentional observations as part of your assessment.

Teachers also consider what they know about students’ out-of-school lives. We integrate this information with classroom kidwatching notes to make decisions about the engagements, materials, or issues that seem most beneficial for student learning. These insights allow us to make classroom decisions that are tailored to students’ specific identities, strengths and needs.

Click HERE to see how Chris Hass connects information from in-school and out-of school settings to make instructional decisions.

Taking a Deep Look at a Small Sample of Student Work

From exit slips and rough drafts to finished papers and 3-D projects, teachers have access to a steady stream of student work. Each sample could be the focus of a deeper study of a student, the task, the larger context in which the task was completed, and/or our own assumptions about how to support and recognize literacy learning.

Click HERE to hear Chris Hass reflecting on the information he gathered from consideration of a classroom artifact of learning.

Spending one block of time looking through a pile of exit slips or any other sample of student work can provide us with enough data to write pages about our students. How can we use the mountain of student learning artifacts effectively?

Click HERE to see one way of reviewing a set of student learning artifacts as an assessment experience.

Click HERE to see the questions teachers might ask when reviewing a set of exit slips.

Reflecting on Conferences with Students

Whether conducted online via Zoom, Skype, or Google Hangout or face to face in the classroom, these conversations offer teachers a rich opportunity to listen to the ways students describe their work. These could be focused on plans and intentions, reflections on the process, or reviews of a final product.

Such conversations help teachers understand what students are doing, how they are getting along with their work, and how to help them. They also provide students with an important opportunity to reflect on and talk about their work, raising awareness of their own thinking, and to consider ways of going about the work of reading or writing.

Click HERE to see a set of questions a teacher might ask when reflecting on a conference or an interview with a student.

Regardless of the decisions about assessment made outside the classroom, teachers can take control of their own assessment tools and strategies. Being intentional about the data selected from the constant flow of information in a classroom setting can help to keep the process manageable and focused on a greater understanding of what we do to support student literacy learning, and why we do it.

Kathryn Mitchell Pierce works with graduate and undergraduate teachers at Saint Louis University, Missouri. Chris Hass is a second- and third-grade teacher at the Center for Inquiry in Columbia, South Carolina.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.