This post was written by NCTE member Adeli Ynostroza Ochoa.

Creating activities where teachers revisit how they were assessed in schools can be a great reflexive tool for generating antiracist practices in which children can see themselves in the curriculum. Assessments are tools that inform teachers about their students’ learning, but the term “assessment” is commonly interchanged with “testing.” A test is a product that measures particular objectives. Meanwhile, an assessment should be used as a process of monitoring student progress.

Chris Hass’s blog post Putting Advocacy on the Ballot in November reminds us of the narrowing of curriculum due to standardized and high-stakes testing that started in 2002 under the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act and continues under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). A major component of ESSA is the accountability related to “English learners” placing emphasis on testing English language proficiency in K–12 education. These tests, however, often dismisses emergent bilingual children’s cultural knowledge and encourages a curriculum of assimilation.

Redirecting how we measure students’ bi-/literacy proficiency starts by understanding our own experiences with reading assessments and most importantly defining what this looks like. First, it is important to bring awareness to social identities and our beliefs related to assessments. Defining and reflecting on the purpose of the assessments could bring the awareness to the overall purpose. Are the assessments being used to evaluate an emergent bilingual’s English language proficiency or content knowledge? Do they capture students’ cultural knowledge connected to their families and communities?

As an instructor in the bilingual teacher preparation program at The University of Texas, I noticed bilingual preservice teachers first referred to assessing as “testing.” In training future bilingual teachers, I wanted to show how assessing emergent bilingual students differed from the common term of “testing” or “standardized testing.” Assessing each child individually and holistically could provide a deeper view on the child’s strengths and the areas needing improvement. With this in mind, I asked the bilingual preservice students to create a reflexive autobiography to provide a view of what they defined as assessing. Highlighting this need, bilingual teacher candidates were asked to prepare a video sharing their first encounters with reading assessments with the objective of showcasing experiences from both the school and the home to generate insights on reading assessments with an appreciative lens towards students. The goals of the video autobiography were to

- recall practices of the home, such as parents asking their children to memorize prayers, rename details of la novela, participate in recipes, or follow instructions;

- generate insights on the purpose and importance of informal literacy assessments capturing all cultural and linguistic repertoires;

- distinguish the difference between a test versus an assessment and build an awareness of balancing formal and informal literacy assessments; and

- advocate for formative literacy assessments as tools in getting to know students and their families. The act of eliciting and sharing memories offers agentic power prioritizing students multiliteracy.

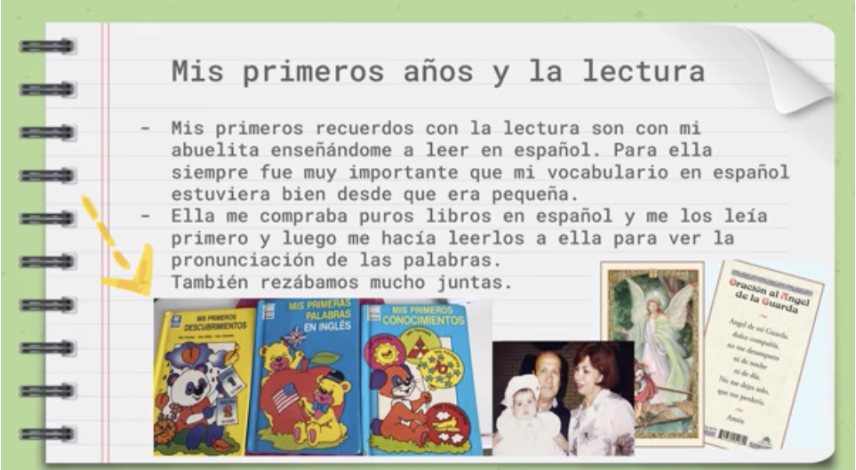

It did not surprise me that every bilingual preservice student included in their biography the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) testing, the state’s testing program based on state curriculum standards in core subjects including reading, writing, mathematics, science, and social studies. Besides including the State’s assessments and district benchmark testing in their autobiography, students also included lived experiences with assessments in their own family practices. Below is an example of a preservice student reminiscing on learning how to read in Spanish but also being evaluated by her grandmother to make sure the Spanish was being pronounced correctly. In addition, the student added a photograph of her grandmother, mother, and a prayer card to memorize the prayer.

Translation:

My first years and reading

-My first memories with reading were with my grandmother teaching me how to read in Spanish. Since I was little, for her it was always very important that my vocabulary in Spanish be proficient.

-She would buy me books in Spanish and would first read them to me and then she would make me read them to her to see if I knew how to pronounce the words correctly.

We also prayed together a lot.

In reframing how we assess students’ reading development in schools, centering formative assessments and including families as experts in their child’s learning and development brings awareness and a path to equity. Therefore, linking assessment practices with the ways parents and family assess literacy at home becomes a bridge between schools and home. Accordingly, to be a bridge “is an act of will, an act of love, an attempt toward compassion and reconciliation, and a promise to be present with the pain of others without losing themselves to it” (Anzaldúa, 2002, p. 4).

As educators, we must advocate for formative reading assessments to be used not for testing but to learn about and know our students.

Reference

Anzaldúa, G. E. (2002). (Un)natural bridges, (Un)safe spaces. In G. E. Anzaldúa & A. Keating (Eds.), This bridge we call home: Radical visions for transformation. Routledge.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.

Adeli Ynostroza Ochoa is a former bilingual teacher and doctoral candidate in curriculum and instruction at The University of Texas at Austin. At The University of Texas at Austin she has taught reading methods, reading development and assessments, teaching young children, and acquisition of language and literacies. Her research areas of interest include funds of identity, intersectional literacy practices, and hybrid identity dynamics in teacher education.

Standing Committee on Literacy Assessment Members: Chris Hass, Renata Love Jones, Bobbie Kabuto, Idalia Nuñez, Kathryn Mitchell Pierce, Peggy O’Neill, Eric Turley, and Elisa Waingort.