The most popular Intellectual Freedom Center blogs for 2018 each scored a place in the top 100 NCTE blogs for the year. Together the blogs focus on texts and students having the right to read texts even if someone might consider the texts uncomfortable or dark; even if some would like to ban the books and silence their stories. For teachers these blogs offer rationales for teaching texts and procedures to follow before and after a challenge. For all readers of these blogs, thank you for keeping many good texts in the hands of your students! The top blogs are as follows.

Uncomfortable Texts

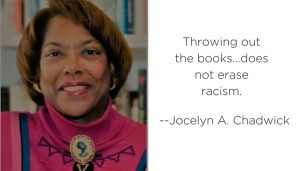

The blog focused on a brouhaha in Duluth, Minnesota, where . . . the superintendent declared that The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird would be removed from the required book list for middle and high schools in the district. NCTE past president Jocelyn A. Chadwick was interviewed on Minnesota Public Radio and noted, “Students should not be made to feel uncomfortable in a classroom, they should be made to feel safe. And safe does not necessarily mean not reading uncomfortable literature . . . just about everything we teach right down to Little Red Riding Hood is uncomfortable. . . . I want a good text.”

The blog focused on a brouhaha in Duluth, Minnesota, where . . . the superintendent declared that The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and To Kill a Mockingbird would be removed from the required book list for middle and high schools in the district. NCTE past president Jocelyn A. Chadwick was interviewed on Minnesota Public Radio and noted, “Students should not be made to feel uncomfortable in a classroom, they should be made to feel safe. And safe does not necessarily mean not reading uncomfortable literature . . . just about everything we teach right down to Little Red Riding Hood is uncomfortable. . . . I want a good text.”

What Do I Do? They’ve Taken the Books Away

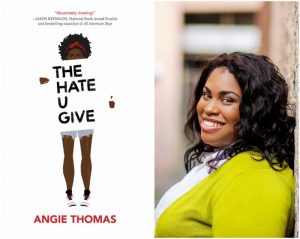

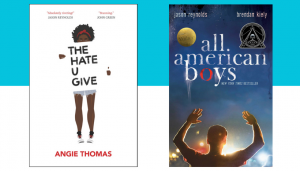

This blog was about a challenge to The Hate You Give in Katy, Texas. “What to do is the first and biggest decision you need to make when a book is challenged, whether in your own classroom, in the district, or elsewhere. Following are a few suggestions:

This blog was about a challenge to The Hate You Give in Katy, Texas. “What to do is the first and biggest decision you need to make when a book is challenged, whether in your own classroom, in the district, or elsewhere. Following are a few suggestions:

• Make sure you have all the facts about the incident.

• Know your district’s policies for selection of texts and reconsideration of texts. You should be able to find these on your district’s website under School Board and School Board Policies.

• Learn about The Students’ Right to Read

• Talk to your colleagues in the district and in your affiliate both about the issue and about how they are thinking about responding to it.

• Contact NCTE’s Intellectual Freedom Center and talk through the challenge.

• Make your decision about next steps. Make the decision that you can live with.”

Selecting Texts for Your Students and Your Course

This blog focused on selecting texts, as whole class reads, to anchor literature circles, or to sit in your classroom library awaiting interested students to check them out. “Selecting texts for our courses is where we begin that most important educational enterprise of connecting students and texts. . . . Make sure you consult your school’s selection policy.” According to NCTE, “The cornerstone of consistent, pedagogically sound selection practices is a clear, written policy for the selection of materials in the English language arts program. Such a policy not only helps teachers to achieve program goals, but also helps schools protect the integrity of programs increasingly under pressure from censors, propagandists, and commercial interests.”

Banning Books Silences Stories

Focusing on the theme of the 2018 Banned Books Week, the blog notes, “Oddly, book challengers believe so strongly in the power of reading that they fear the impact a story might have on their child or even on their community. They fear the reality—even in fiction—of the people in the books who are different from themselves, who speak and behave differently, who have different ways of thinking.”

Focusing on the theme of the 2018 Banned Books Week, the blog notes, “Oddly, book challengers believe so strongly in the power of reading that they fear the impact a story might have on their child or even on their community. They fear the reality—even in fiction—of the people in the books who are different from themselves, who speak and behave differently, who have different ways of thinking.”

When a Good Book Helps the Conversation

Focusing on the charge from the Fraternal Order of Police in Charleston County, South Carolina, to The Hate U Give and All American Boys for being “anti-police” books, and their request that the books be removed from the Wando High School summer reading list, the blog notes, “Kids are talking . . . about race and about the many instances in the last few years in which African American youth have been killed by police. They’re listening and watching movements like #BlackLivesMatter. Kids are trying to understand, trying to find their own voices, and to find ways that might help this violence not happen. This is when a good book helps the conversation.”

Focusing on the charge from the Fraternal Order of Police in Charleston County, South Carolina, to The Hate U Give and All American Boys for being “anti-police” books, and their request that the books be removed from the Wando High School summer reading list, the blog notes, “Kids are talking . . . about race and about the many instances in the last few years in which African American youth have been killed by police. They’re listening and watching movements like #BlackLivesMatter. Kids are trying to understand, trying to find their own voices, and to find ways that might help this violence not happen. This is when a good book helps the conversation.”

An Argument for the Dark Side of Literature for Young People

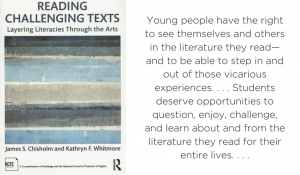

The bottom line is that we owe our young students texts that, as Renita Schmidt says in her chapter (p. 91) of the NCTE book Reading Challenging Texts: Layering Literacies Through the Arts,“help children and young adults learn about the world and consider ethical decisions people make within human circumstances, . . . that require sensitivity and empathy from anyone who reads them, talks about them, or uses them to understand more about who they might become in the world.”

Authors Speak Out on Reading without Censorship

Quotes from ten authors who talk about why students need to read widely, especially those books that some adults may find troubling. For example, from Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple and In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,“Great Literature is help for humans. It is medicine of the highest order. In a more aware culture, writers would be considered priests.”

Quotes from ten authors who talk about why students need to read widely, especially those books that some adults may find troubling. For example, from Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple and In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens,“Great Literature is help for humans. It is medicine of the highest order. In a more aware culture, writers would be considered priests.”

Real Students, Real Writing

“Censorship of writing not only stifles student voices but denies students important opportunities to grow as both writers and thinkers. (NCTE Beliefs about the Students’ Right to Write) “I know that while the [3-paragraph and 5-paragraph] formulas took away the students’ voices, they also erased their own diversities and the knowledge, values, and experiences they brought with them to school. I know that the intersection of NCTE policies on intellectual freedom, writing, and diversity form the backbone of how we should teach writing.”

“Censorship of writing not only stifles student voices but denies students important opportunities to grow as both writers and thinkers. (NCTE Beliefs about the Students’ Right to Write) “I know that while the [3-paragraph and 5-paragraph] formulas took away the students’ voices, they also erased their own diversities and the knowledge, values, and experiences they brought with them to school. I know that the intersection of NCTE policies on intellectual freedom, writing, and diversity form the backbone of how we should teach writing.”

Being Challenged by Challenging Texts

“James S. Chisholm and Kathryn F. Whitmore, authors of the recent NCTE book Reading Challenging Texts: Layering Literacies Through the Arts, point out that the more ways we look at literature, the more we involve ourselves in the literature, the more we learn about it, ourselves, and our community. They recognize that to decide to read such literature with students is an act of professional courage. Every student has the right to read and the ‘freedom to explore ideas and pursue truth whenever and however they wish’ (NCTE). Furthermore, young people have the right to see themselves and others in the literature they read—and to be able to step in and out of those vicarious experiences. And . . . students deserve opportunities to question, enjoy.”

“James S. Chisholm and Kathryn F. Whitmore, authors of the recent NCTE book Reading Challenging Texts: Layering Literacies Through the Arts, point out that the more ways we look at literature, the more we involve ourselves in the literature, the more we learn about it, ourselves, and our community. They recognize that to decide to read such literature with students is an act of professional courage. Every student has the right to read and the ‘freedom to explore ideas and pursue truth whenever and however they wish’ (NCTE). Furthermore, young people have the right to see themselves and others in the literature they read—and to be able to step in and out of those vicarious experiences. And . . . students deserve opportunities to question, enjoy.”

But for a Word

“If you end up in a conversation with a parent about certain language in a text, listen, but reframe their complaint around the meaning of the whole text and why you chose this text to meet the goals of the curriculum for the course. Try to help them understand that your criteria for selection is not at all about counting pieces but rather about total essence, including how kids will connect with the text and be able to use it first for itself and then as a jumping-off point to other meaningful learning activities.”

“If you end up in a conversation with a parent about certain language in a text, listen, but reframe their complaint around the meaning of the whole text and why you chose this text to meet the goals of the curriculum for the course. Try to help them understand that your criteria for selection is not at all about counting pieces but rather about total essence, including how kids will connect with the text and be able to use it first for itself and then as a jumping-off point to other meaningful learning activities.”

The Honesty of Sadness in Literature for Young People

“Time magazine featured articles from two favorite writers of stories for young people, Matt de la Peña and Kate DiCamillo. The articles argued for the need young people have to read stories that are real, stories that mirror their lives and/or the lives of others, stories that present the honesty of sadness. And they argue for authors who aren’t afraid to show emotion in their writing and when they’re standing in front of an auditorium of kids. . . . Who are we fooling when we think kids can’t take a little sadness?”